ALIGNING THE 'INNER SKELETON'

by Stephen G. Michaud

Therapy treats the body's fascia to address a wide range of medical problems

Three years ago, Donna Emery of rural Covington was violently assaulted in her home. Her assailant beat the psychologist, shot her in the head and left her to die, which Ms. Emery nearly did.

In the aftermath of the attack, her multiple disabilities included an immobilized torso and left arm, the consequence of lying on her dining room floor in a state of semi-consciousness for nearly 24 hours.

A battery of therapists tried to relieve the wheelchair-bound victim's paralysis using several regimens, including heat, massage, and ultrasound. Nothing worked. "They didn't have a clue what was wrong with me," Ms. Emery says. "It felt as if I'd turned to stone."

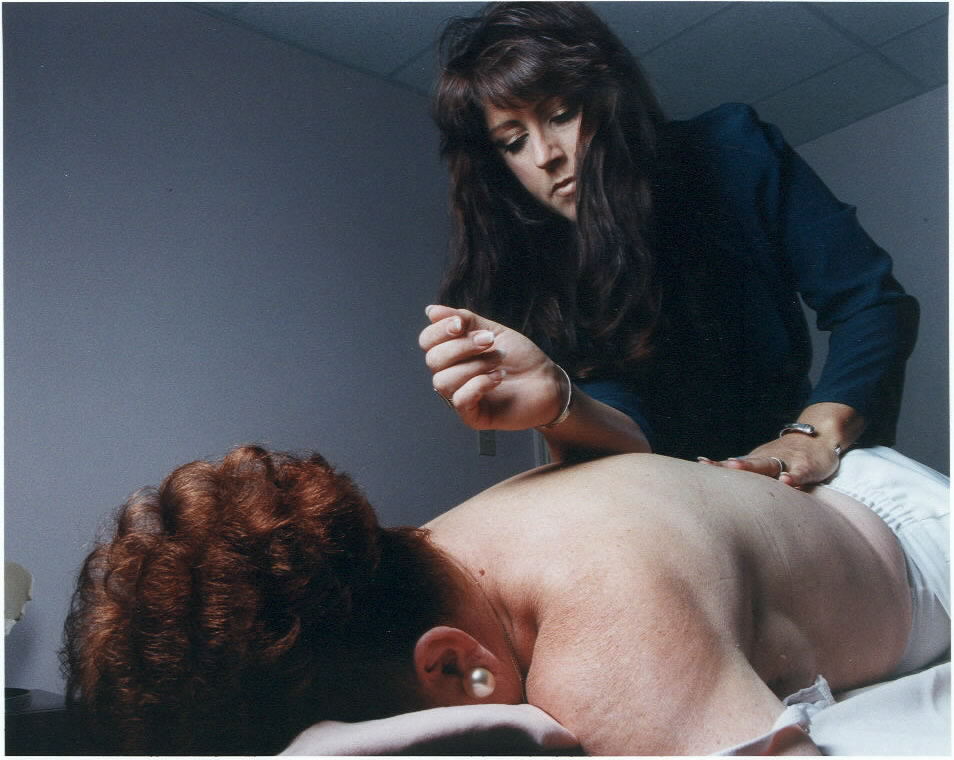

Then a physician referred her to Frankie Burget, an occupational therapist who is one of the area's few highly trained specialists in a little-known therapy called myo-fascial release, or MFR. In a matter of weeks, Ms. Burget had restored full 180-degree motion to Ms. Emery's left arm and -- for the first time in nearly a year -- the patient was turning her head without moving her entire trunk.

"I could feel the release as she worked on me," says Ms. Emery. "If it were not for MFR, I'm sure I'd still be in a wheelchair."

Myo-fascial release, which takes its name from the Greek word for muscle, plus fascia, the tough filmy-white connective tissue that sheaths and surrounds muscles, is an old practice finding newfound popularity as a treatment for conditions as acute as Ms. Emery's and as chronic as fibromyalgia, the mysterious (possibly auto-immune) and painful neuro-muscular condition thought to afflict millions of women, particularly those at menopause.

Ms. Burget has used MFR techniques to relieve conditions as various as cerebral palsy, stress, spinal cord injuries, sinus headache, temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ) -- even bowel disease and the injuries a utility lineman suffered from electrical shock.

"The key is to allow the body to tell you, the therapist, what it needs," says Ms. Burget, who lives in Euless. "I follow the body. I do not force it."

Whether or not there's a close casual link between healthy fascia and general well-being is where MFR diverges from traditional medicine.

Current medical thinking does not discount fascia's structural importance. The American Medical Association's Encyclopedia of Medicine gives "fascia" a one-paragraph entry, defning it as fibrous connective tissue that surrounds many structures of the body. One layer of the tissue, the encyclopedia says, envelops the entire body just beneath the skin. Other layers enclose muscles and soft organs.

Fascial Flaws

Whereas traditional medicine views the tissue as essentially inert, MFR therapists have a different view. They say much human pain and suffering is traceable to flaws in the fascial system. They see the tissue as an endless, three-dimensional ribbon, a sort of interior body stocking that provides shape, protection and structural integrity. Without fascia, a human would crumple into a lumpy bag of skin and bones.

John Barnes, MFR's leading theorist, who also has developed many of its techniques (and also trained Frankie Burget) puts it this way: "When you get myo-fascial restrictions, it's the equivalent of that internal body stocking being knotted. In turn, the tissue inside becomes twisted and shortened and all the nerves and blood vessels that pass through that three-dimensional web are crushed."

Both the fascia and the "ground substance" -- Mr. Barnes' term for the chemically complex fluid associated with the fascial system -- are susceptible to damage from injury, inflammation and stress. Ms. Burget, for example, describes Donna Emery's condition as akin to a massive snarl -- "Think of a truck driving through a chain-link fence," she says -- which had to be unsnarled one painstaking step at a time.

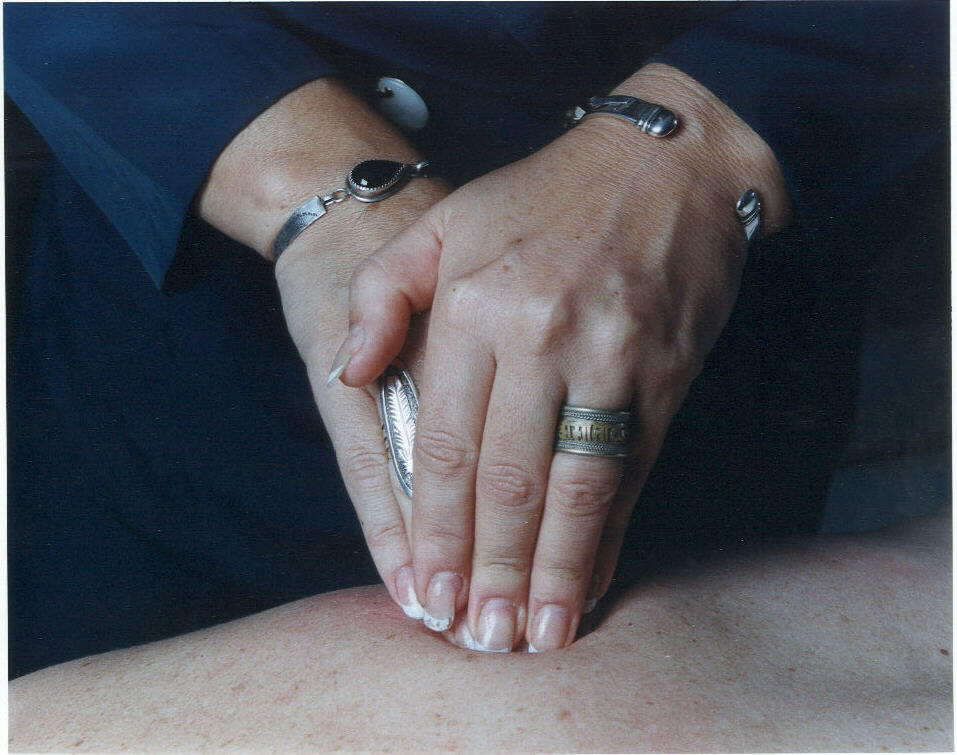

Unlike related therapies, MFR involves little rubbing, kneading or pounding. There also are no charms or amulets employed, no chants or incense, nor any substances to ingest. Rather, the therapist indirectly scuplts the fascia as if it were taffy, slowly pulling, torquing or pushing at it through the skin, exerting constant, even pressure all the while. The object is to free up the "ground substance" and to break or release the tangled fibers of fascia -- sort of like shutting your eyes and donning mittens to untangle a sticky wad of Velcro sheets in a bag.

Mind-body feedback

Like proponents of other therapies, most notably chiropractic, MFR practitioners believe cognition is not restricted to the mind, that there is a mind-body feedback loop. According to Ms. Burget, memory of certain, usually traumatic events, such as car accidents, can be stored in the tissue, and these experiences are therapeutically retrieved and relived in the course of MFR therapy.

As Ms. Burget explains it, the fascia acts as a sort of recording device, capturing a wince, a twist, a recoil or an outright wound. Even decades later, an MFR therapist may happen onto the knot, or adhesion, where the experience is stored. The act of releasing the restriction triggers vivid recollections of the episode that caused it, sometimes complete with auditory and olfactory stimuli. In unwinding, a whole series of these stored traumas may release serially, creating cathartic moments of both pain and pleasure. Donna Emery remembers crying as she underwent unwinding with Ms. Burget.

While much of MFR's conceptual framework awaits scientific confirmation -- fascia is eerily protean material, abundant to the naked eye at autopsy, invisible on X-rays -- the therapy's substantive benefits have won Frankie Burget an enthusiastic following in North Texas.

"She's very good at it," says Tommy Overman, clinical director of the Dallas Spinal Rehabilitation Center on Harry Hines Boulevard, where Ms. Burget worked in the early 1990's. "I believe in the concept of MFR, and I know that Frankie is an excellent therapist."

Dr. Elizabeth Vliet, a specialist in preventive and climacteric medicine, which focuses on midlife health issues such as hormone-induced changes, visits Ms. Burget for treatments herself and often refers patients.

"I've used MFR therapy for pain management for myself and for my patients for 15 years," says Dr. Vliet. "I've had three back surgeries. I doubt I'd have the strength, flexibility and freedom from pain that I do without myo-fascial therapy."

Many of Dr. Vliet's patients are middle-aged women suffering from fibromyalgia and isolated back and hip pain, she says. "Hormone changes at midlife tend to trigger changes in the connective tissue and muscles that make women more susceptible to muscular-skeletal pain syndromes," she says. "Myo-fascial release is superb for these kinds of problems. Frankie is extraordinarily skilled at it, too. It's like playing the piano. You can be trained or you can be gifted. Frankie is both."

Among Ms. Burget's youngest patients has been Christopher, who at age 15 months developed a turned-in left leg. The only way Christopher could walk was if he pushed something for balance. Even so, the toddler dragged the top of his left foot as he went along.

His mother, Karla, an occupational therapist herself, knew of John Barnes' theories, and wanted an MFR specialist to treat her little boy. Christopher's pediatrician obliged his mother with a prescription. However, Karla says she could find no therapist competent enough to administer MFR to her son within her insurer's network, so she sought out Frankie Burget, whom she and her husband, Mark, have compensated out of their own pockets.

Ms. Burget evaluated the boy and noted immediately that he did not move his hips when he tried to walk, a strong clue to her that Christopher's problem was centered in his pelvis, not his bad foot. She believed his stiffness was caused by myo-fascial restrictions, possibly developed during birth. Whatever caused the myo-fascial restrictions, she set about releasing them, a once-a-week process that consumed most of a year.

"We thought of it as an investment in his future," says Karla, who reports that the therapy was a complete success. "Christopher's fine now. He's happy and running around and climbing as if there never was a problem at all."

( Reprinted with permission from the Dallas Morning News, August 9, 1999 )